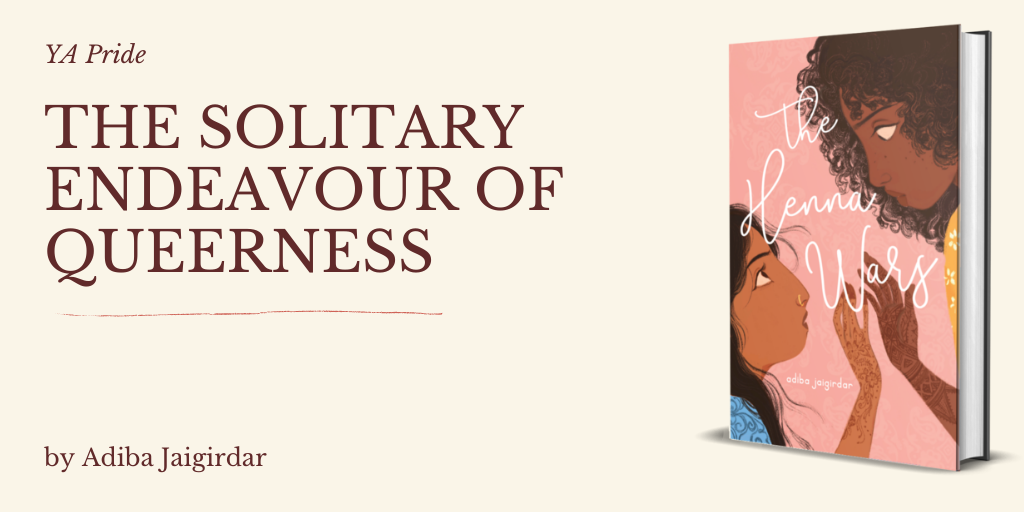

by Adiba Jaigirdar

Growing up queer can feel really lonely in a lot of ways. It can feel lonely in that you don’t even realise you are growing up queer. It can feel lonely in that when you do realise you’re queer, you don’t know if you’re allowed to be. Because you’re Asian, and you’re Muslim, and those things seem like an antithesis to queerness. All the queer people you have ever known have not looked like you. All the queer people in TV or movies or books have not looked like you. So surely…you can’t be queer?

And then when you realise that yes, you can be queer, you’re not sure if you’re allowed to speak about it. If you’re allowed into queer spaces occupied people who don’t look like you, and who do consider your identity an antithesis to queerness. Sometimes, you may feel like you have to choose. Do you want be Asian, Muslim, or queer? Because all of those things together just don’t fit together. Or so some people seem to think so.

If you’ve ever felt any of the above, you are not alone! I’ve felt like that for most of my life, and I’m still trying to figure out how to navigate all of that. It feels like for most of my life I’ve been trying to figure out how not to feel overwhelmingly lonely in my experience of the world, and I think writing and publishing my debut The Henna Wars, has finally helped me do that.

You might think that strange, because writing a book is a solitary endeavour. It’s sitting in front of your computer, or with a notebook, and closing yourself off from the world around you so that you can enter the world you’ve created within your book. But in a strange way, writing this book has opened me up to more positive connections than I ever could have imagined.

You might think that strange, because writing a book is a solitary endeavour. It’s sitting in front of your computer, or with a notebook, and closing yourself off from the world around you so that you can enter the world you’ve created within your book. But in a strange way, writing this book has opened me up to more positive connections than I ever could have imagined.

When I sat down to draft The Henna Wars for the first time, I wasn’t thinking about agents and editors, and publishing. I was thinking about this story in my head that seemed desperate to be told, these characters who were both reminiscent of my teenagerhood, and not at all reminiscent of it at the same time. And it was only after I had finished writing that the familiar doubts that I had about my identities all my life began to rise to the surface. Was this a book I was allowed to write? Was I queer enough for it? Was it too much to write about two brown girls who happened to fall in love? Was it too much to give them a happy ending?

I began to send out early drafts of The Henna Wars to my critique partners and beta readers. Most of them were queer POC themselves. Of course, they gave me critique and feedback that helped me make my story better, but they also helped me assuage my doubts. Like me, they had rarely seen stories about brown girls who were allowed to fall in love and love their culture and be happy.

Before The Henna Wars went on submission, I received a reader report from someone who had recently come out to their family. They said they had never read representation like this before, and the book had brought tears to their eyes. Of course, that message brought tears to my eyes, and it made some of those feelings of loneliness dissipate. Even though I didn’t know this person’s name, or anything about them, this book I had written was somehow tying us together in our experiences.

When I received my first round of revisions from my now-editor, one of the tiny comments she left on my manuscript was “my perpetual mood in high school,” in a scene where Nishat, my main character, is questioning the heterosexuality of the love interest’s actions. It’s a small thing, but it’s probably one of my favourite moments of revising The Henna Wars. It felt strangely enthralling to know that Nishat (and also me) is not asking these questions in isolation. So many of us have been there, but it’s not always easy to recognise that or acknowledge it.

The day that The Henna Wars came out felt a little surreal. Not because the book was out in the world (a little bit because of that…), but because of all of the people who kept saying, “this is a book about someone like me!” or asking, “this is a book about someone like me?” as if they had never expected something like this to exist. I can relate—because I had never expected something like this to exist too. Not something that felt palpable to me, to my life, to the experiences of the people around me. And to see others express surprise, and joy, that this could also be representative of their experience, that made me feel infinitely less alone.

Now that The Henna Wars is out in the world for readers to buy from bookshops and borrow from their libraries and read, read, read, I occasionally see people sharing similar sentiments about the ways that they can relate to this story. Or the ways in which they had never quite seen a representation of their experience before. Or the ways in which this book made them feel warm and happy. Recently, I received a message from one such reader, and they said that they had thought they couldn’t write about queer women of colour. That if they did, they didn’t know that there would be people who wanted to read it. But now that they had read my book, they thought maybe they could do that, and people would want to read their stories.

So, yes, it can definitely feel lonely to grow up queer (especially when you’re a queer person of colour), and sometimes it can also be lonely when you’re all grown up and queer. But writing this book and putting it out into the world, has made me feel so much less lonely, and I can only hope that it has done the same for other queer people of colour too.

—

Adiba Jaigirdar was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and has been living in Dublin, Ireland from the age of ten. She has a BA in English and History, and an MA in Postcolonial Studies. She is a contributor for Bookriot. All of her writing is aided by tea, and a healthy dose of Janelle Monáe and Hayley Kiyoko. When not writing, she can be found ranting about the ills of colonialism, playing video games, and expanding her overflowing lipstick collection. She can be found at adibajaigirdar.com or @adiba_j on Twitter and @dibs_j on Instagram.

Adiba Jaigirdar was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and has been living in Dublin, Ireland from the age of ten. She has a BA in English and History, and an MA in Postcolonial Studies. She is a contributor for Bookriot. All of her writing is aided by tea, and a healthy dose of Janelle Monáe and Hayley Kiyoko. When not writing, she can be found ranting about the ills of colonialism, playing video games, and expanding her overflowing lipstick collection. She can be found at adibajaigirdar.com or @adiba_j on Twitter and @dibs_j on Instagram.